Share this Article

Nepal is often romanticized for its majestic mountains and ancient temples. Yet, beneath the silhouette of the Himalayas lies an equally compelling narrative: the story told by the very walls we live within. Traditional Nepali homes, built from mud, brick, wood, and stone, are more than structures — they are archives of history, vessels of culture, and living embodiments of the societies that construct them. Each beam carved, each window etched, and each courtyard constructed carries meaning beyond functionality. This article delves into the intricate relationship between architecture and identity in Nepal, exploring how traditional homes reveal insights into caste, religion, gender roles, environmental adaptation, and cultural continuity.

I. Architecture as Social Language

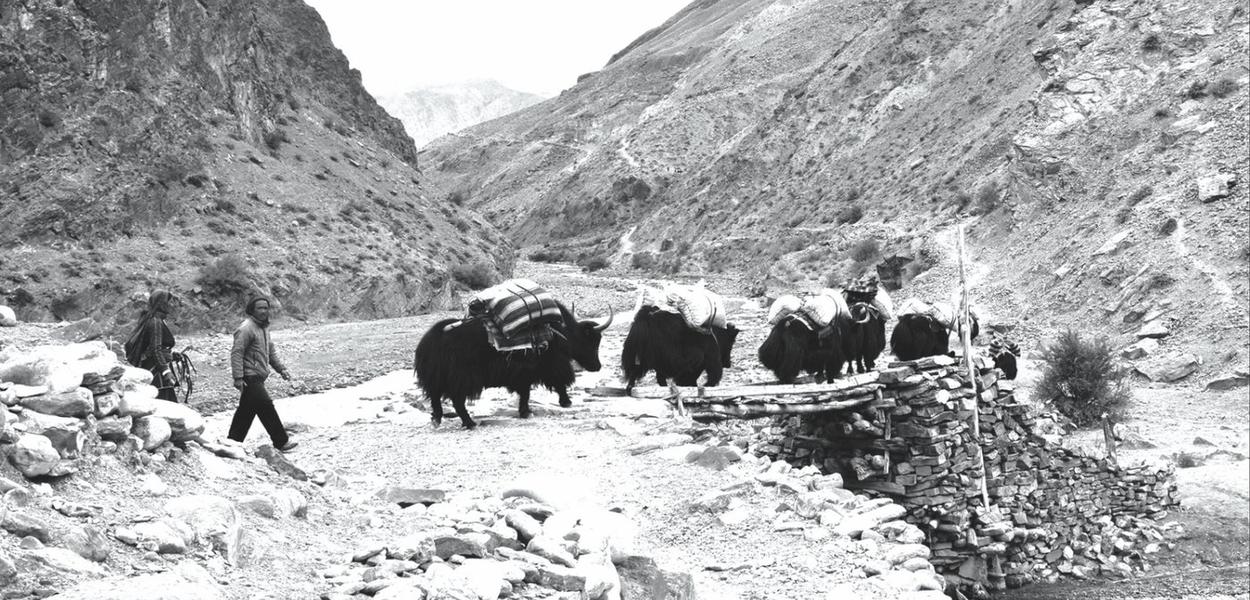

Traditional Nepali architecture is not homogenous. Instead, it varies drastically between the flatlands of the Terai, the mid-hills, and the high Himalayas. These differences are not merely ecological; they reflect sociocultural distinctions.

For example, Newar homes in the Kathmandu Valley, with their brick facades and ornately carved wooden windows (tikijhya), differ from the stone dwellings of the Thakali in Mustang or the bamboo and mud houses of the Tharu people. Each structure is an architectural dialect, shaped by community-specific aesthetics, belief systems, and social structures.

In Newar culture, architecture reflects social hierarchy. Wealthy merchant families may have five-storied courtyard houses with central wells, while poorer artisans may live in single-room row houses. The orientation of the home — where the kitchen lies, where the puja room is placed, and even the number of floors — is often determined by caste and ritual purity.

II. Gender and Domestic Architecture

The spatial design of traditional Nepali homes often mirrors gender roles. In many communities, the kitchen is a sacred yet restricted space where only women may enter. Meanwhile, the ground floor (or outer verandah) is a public male domain where guests are received.

In Newar homes, the uppermost floor (called the "mataa") is reserved for worship and ritual activities, sometimes off-limits to menstruating women. In contrast, Tharu homes in the Terai allow more communal sharing of space between genders, reflecting different customs and social codes.

Moreover, the act of home-building itself is gendered. Women in rural Nepal often participate in the construction of mud walls, thatching of roofs, and decoration with rice flour or cow dung patterns. These designs, often seen as "mere aesthetics," are actually coded expressions of protection, fertility, and cosmology.

III. Sacred Geometry and Ritual Space

Traditional homes in Nepal often align with sacred geometries. Builders frequently consult astrologers or priests to select an auspicious site, and construction begins only after elaborate rituals — such as digging a symbolic foundation pit and placing sacred objects or grains to appease deities.

The main entrance is typically flanked by protective symbols like swastikas, lions, or tantric mandalas. The use of the toran (decorative cloth or wooden lintel) above the door is believed to ward off evil spirits.

Inside, the puja kotha (worship room) is often a small alcove but spiritually central. Its placement and the direction it faces vary depending on community and sect — Hindu, Buddhist, Bon, or animist. These sacred spaces anchor the home within the cosmic order.

IV. Oral Histories Encoded in Wood and Earth

Many older homes in Nepal feature lintels, beams, and columns etched with scenes from local folklore, epics like the Ramayana, or tantric deities. These are not mere decoration but a method of storytelling in a historically non-literate society.

For instance, in Bhaktapur and Patan, you might find carved panels depicting Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, flanked by peacocks and serpents — a visual prayer for prosperity and protection.

In Limbu and Rai homes, ancestors are represented not with icons but with clan-specific markings, rituals, and even stored relics like jewelry or bones kept in attic spaces. In this way, the home becomes a shrine, a museum, and a mausoleum.

V. Environmental Adaptation and Sustainability

Traditional homes are ecological marvels. In Mustang, the flat-roofed stone structures are built to retain heat and resist wind. In humid regions like Chitwan, homes are lifted on stilts to avoid flooding and snake bites.

Materials are always locally sourced: mud, cow dung, thatch, bamboo, wood, and river stone. These are not only sustainable but also create a thermal balance — cool in summer, warm in winter.

Furthermore, maintenance of these homes is a communal act, often tied to festivals. Before Dashain, for example, families re-plaster walls with a mixture of red mud and cow dung, a ritual that blends hygiene with spirituality.

VI. Urbanization and the Crisis of Continuity

The charm of these whispering walls is under threat. Concrete replaces clay; rebar replaces timber. In cities like Kathmandu, the demand for real estate and earthquake-resilient structures often overrides heritage.

Many younger Nepalis now prefer apartments or modern-style bungalows, often for reasons of prestige, convenience, or necessity. Traditional homes, with their dark interiors and maintenance requirements, are seen as outdated.

This shift is not just architectural; it signals a disconnection from ancestral memory, ecological knowledge, and community networks.

VII. Revival and Reinvention

Despite these challenges, there is a growing movement to preserve and reinterpret traditional architecture. Conservationists in Bhaktapur and Bungamati are restoring heritage homes using ancient methods. Some entrepreneurs are converting old homes into boutique guesthouses, combining modern amenities with traditional aesthetics.

Young architects from institutions like the Nepal Architecture Archive and Kathmandu University are documenting vanishing techniques, materials, and layouts. They advocate for “vernacular modernism” — blending the old with the new in sustainable ways.

Moreover, rural tourism initiatives now encourage travelers to stay in homestays where they can experience traditional architecture firsthand — from sleeping on straw mats to bathing in communal stone taps.

VIII. Conclusion: Listening to the Walls Before They Fall Silent

Traditional Nepali homes are not just about shelter; they are about structure — social, spiritual, and symbolic. They teach us about coexistence with nature, respect for ritual, and the unseen hierarchies of society.

To let them vanish without record is to silence centuries of wisdom encoded in wood and earth. But to restore, reinterpret, and respect them is to keep alive the whispered stories of our ancestors — and perhaps add our own.

In the end, the question is not just what kind of homes we want to build, but what kind of stories we want to tell — and live within.

Categories:

Lifestyle & Local Life

,

Traditional Tools and Utensils

Tags:

WildFlavorsNepal

,

ForgottenFlavors

,

Nepal2025

,

MountainFuture

,

ParaglidingNepal